Talking with ChatGPT about schizophrenia

Another round-up of the most interesting new publications in mental health. Also this week: two new papers on internet use, and the NEJM gets uncanny.

Talking with ChatGPT about schizophrenia

A group of researchers decided to ask chatbots questions about people with schizophrenia, and found that the answers were… more or less okay.

Given the prevalence of negative views towards [people with schizophrenia], we expected stereotypes of violence and the desire for distance to frequently permeate into chatbots. We found limited evidence of stereotypes of violence in chatbots’ answers and less evidence for answers reflecting a desire for social distance from [people with schizophrenia].

If anything, the guard rails might be a bit high: for example, ChatGPT-4 refused to generate an image of a person with schizophrenia, citing violation of content policy (it was perfectly happy to produce images of a person with cancer, depression, or ADHD).

It’s hard to say why ChatGPT and its robot friends have a comparatively enlightened attitude towards mental health problems; this could represent the success of anti-stigma messaging, careful curation by AI companies, or both. It would be useful to know a bit more about what material the chatbots are working with, but I’ll take this as a good news story.

The internet and mental health: time to focus

Two recent publications on the internet and mental health have come to my attention this week. They’re about quite different things, but I get the same message from both.

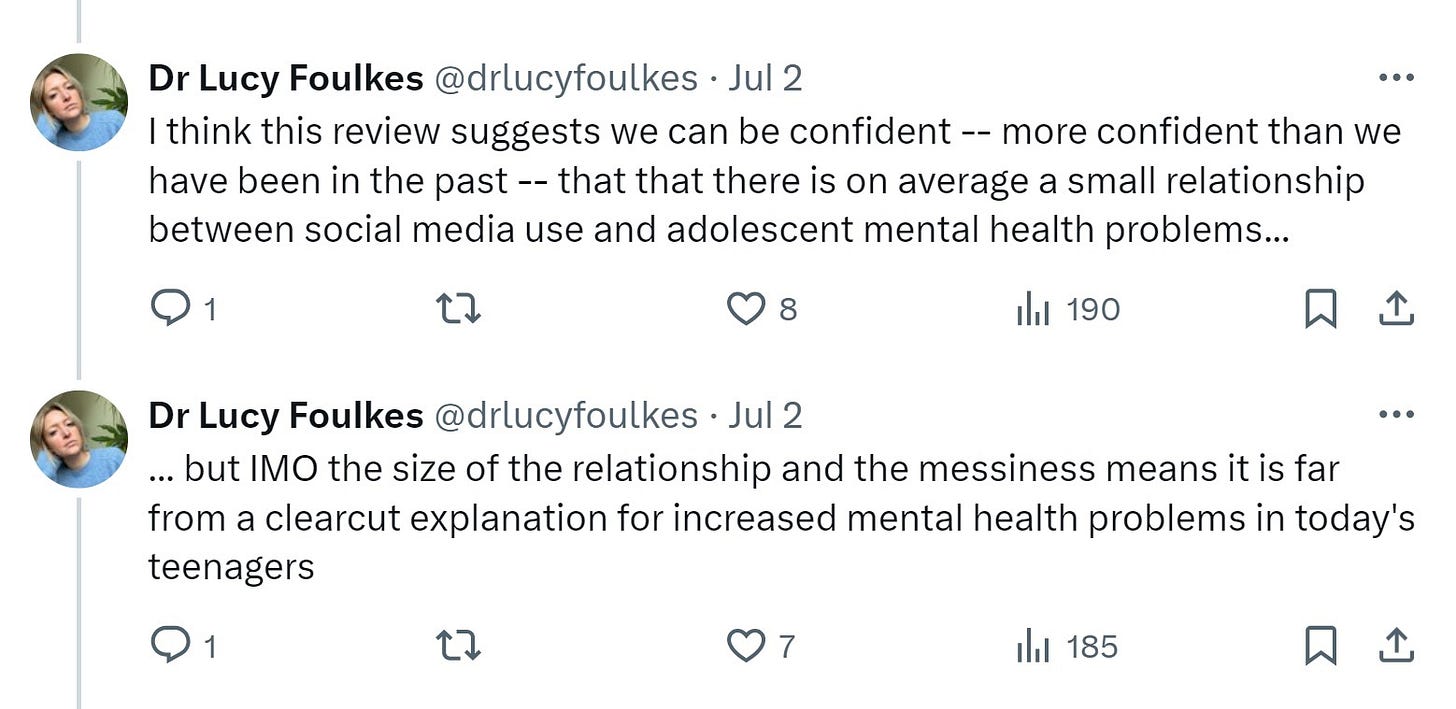

First, there’s this systematic review and meta in JAMA Paediatrics on “Social Media Use and Internalizing Symptoms in Clinical and Community Adolescent Samples”. Lucy Foulkes has written a great X/Twitter thread on this, with which I largely agree. In brief, while the combined data points messily towards an association between social media use and internalising symptoms (meaning experiences such as sadness, anxiety and loneliness), almost 90% of studies included were in the community, as opposed to clinical samples. So while it’s tempting to look at this paper and say “I told you, it’s the phones”, there just isn’t enough data that social media use is the main driver behind rises in diagnosable mental health conditions.

Second, The Lancet Regional Health Europe has published a case series on suicide-related internet use (SRIU) by mental health patients in the UK who died by suicide (fig 1 expands on what SRIU consists of: mostly obtaining information on methods, visiting pro-suicide websites, and communicating suicidality online). As one would expect from the Manchester group, this is a detailed, cautious, and sober appraisal of the evidence. In brief, of 9875 of a sample of 17,347 patients for whom the presence of absence of SRIU could be assessed, SRIU was known to be present in 759 (that’s 8% of the 9875).

Those who had a history of SRIU, as opposed to those without, were more likely to have diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, a history of recent self-harm, use less common methods of suicide, and to have died on a “salient date” (eg, birthday or anniversary). One of the most important findings, however, is that while there is a lot of focus on young people, internet use, and suicide in the media, the numbers show that SRIU also happens in older people; in fact, “the majority of the group with any known SRIU was aged between 25 and 64”.

The authors recommend that clinicians ask about SRIU among patients with mental illness, particularly in those with a diagnosis of autism and recent self-harm. Clinicians should also be aware of the association between SRIU and choice of less common methods, and not be prejudiced by age.

My take-home message from both papers: if we’re trying to figure out the relationship between internet use and mental health outcomes, in addition to grand theories of everything we really need to focus on the precise impact on the most vulnerable groups.

Surgical spirits: a post-transplant ghost story

And finally… a very unusual item in NEJM: a ghost story about a man who had a liver transplant. The donor was deceased, but apparently this did not stop them turning up in the recipient’s hospital room. The uncanny rarely manifests in high-impact journals, unless you count The Lancet’s brief Arthur C Clarke's Mysterious World-style interest in near-death experiences and the power of prayer around twenty years ago.

The NEJM, of course, does not propose that ghosts actually exist. Rather, the author, John Guzzi, posits a psychological mechanism (I’m assuming that, in a patient with new-onset post-op hallucinations, he excluded delirium):

If I’m right, that phantom may have represented more to him than just his organ donor. As he described the Pink Floyd concert his mother had taken him to as a child, he remarked that it was “the only good thing she ever did for me.” This and other hints about an unsettled childhood and strained relationships made me wonder whether his ghost could have been a coping mechanism for overcoming his past traumas, an ethereal guide as he faced the daunting prospect of protecting a transplanted organ over the long haul, with a shaky support system.

Whether that’s true or not, it’s good to see an anaesthetist taking an interest in the unconscious, in the psychological sense of the word.